Antifascist Spirits: Mention and Remember

The text that follows presents fragments of a lecture-performance in which I connect, on the one hand, women's anti-fascist resistance during World War II (partisan movement) and the history of my own family, some of whom were victims of the Jasenovac concentration camp as well as resistance fighters against fascism, and, on the other, my experience as a refugee in the 1990s and the anti-war feminist movement in Former Yugoslavia during the wars in the 1990s.

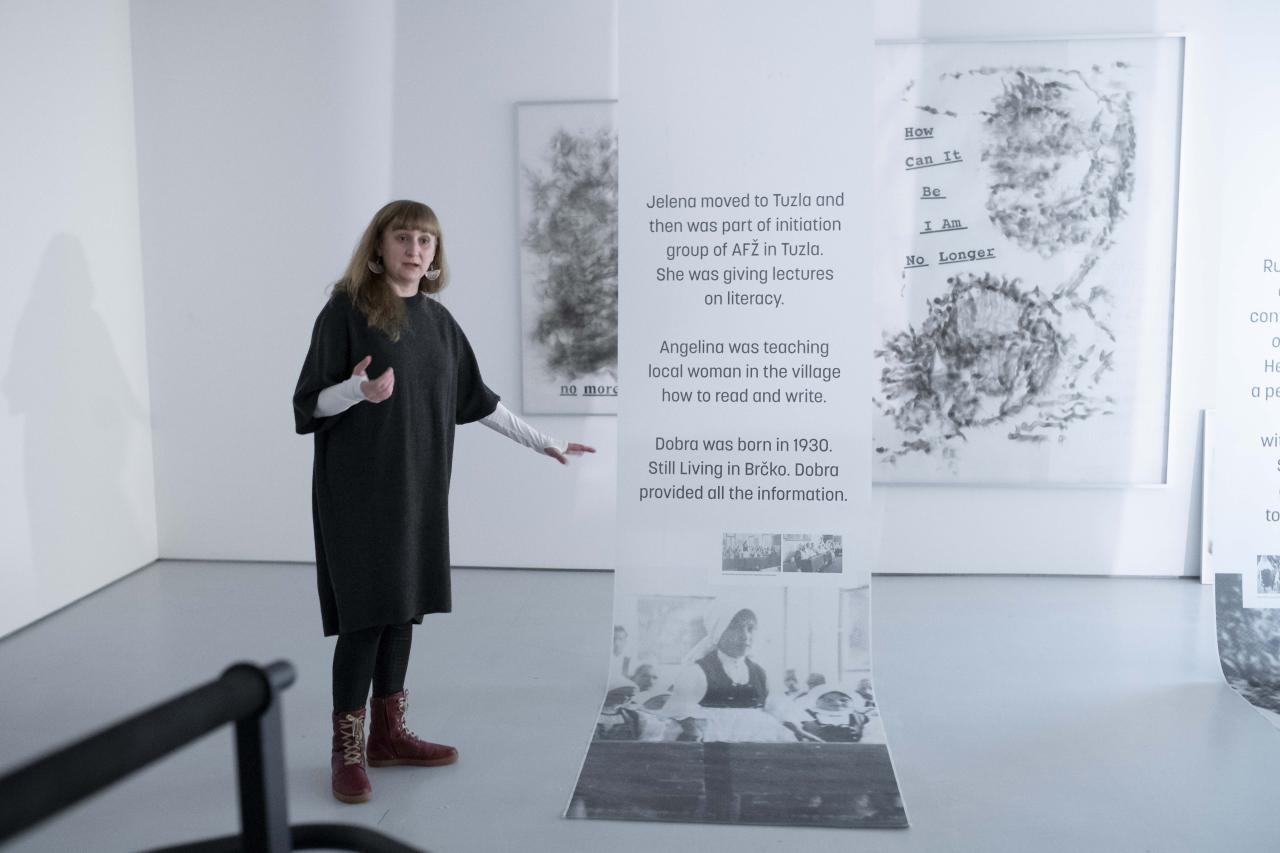

My narrative discusses historical events, my personal and my feminist background. Through a combination of performance, personal narrative as testimony, and a pedagogical approach, I aim to make an anti-fascist and feminist intervention in Austrian art institutions1 where I perform turning the audience into accomplices.

My feminist story begins in 1994, when, as a refugee in Belgrade, I was lucky enough to have direct friendship relations with feminist and anti-war protagonists. I was able to enter the circle of the peace movement and felt HOME for the first time since the beginning of the war in Bosnia.

I met Neda Božinović (1917-2001) in the apartment of a women's organization that same year. This apartment became a self-organized space where refugees and displaced people, activists, and supporters from all over the world met… It was a home, a place for those who were in danger, war deserters, like my friends Stevan, Saša, and the first gay activist Dejan Nebrigić.

Neda was there for all of us. Neda was a shelter for us. I didn't know much about her during the first meetings, but from her attitude I sensed that, besides ideology, she carried a great anti-war experience and a determined struggle.

I remember her blue classic skirt as she sat cross-legged, her gray-black hair tied first in a braid and then in a chignon, and her piercing eyes. I remember her smile that told many stories. She spoke clearly, directly and although I was a teenager at the time, she always addressed me with great respect.

One of the first and most significant anti-war and anti-fascist feminist groups in the 90s, when I met Neda, was Women in Black (Belgrade). Neda was one of the founders.

The group used street performances to show their opposition to the Milosević regime and the war. They emphasized three elements in their performances: using the presence of women’s bodies to express disobedience, dressing in black to mourn the victims of war, and using silence during protests. As the years progressed, actions from Women in Black, among others, became more focused on the roles of borders – national, bodily, EU, etc.

In 1999, the action Women Crossing Borders was initiated by Žarana Papić, in which a huge number of women gathered, including victims of the Srebrenica genocide who had vowed earlier to never cross the border to Serbia, to travel together by bus throughout the region. “The principle is to cross the borders.” (Zaharijević, 2022, 134-138)

This principle formulated by Žarana Papić at the beginning of the wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, was transformed into a long journey across borders, as written in the edition The Never - Ending Quest for Sense: Woman and Peace building in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia where Dubravka Stojanović, quoting Zlatiborka Popov-Momčinović, writes: “across the borders of states, borders of gender, borders of gender essentialisms, borders of comfort…“ (Stojanović, 2022, 11-15).

“The two most important collections documenting the history of the feminist movement in Serbia and Yugoslavia since the 1970s are the legacy of Neda Božinović (1917–2001) and Žarana Papić (1949–2002)“, (Donert Celia, Kerenji Sabina, Kulick Oryisia, and Lorand Zsofija, 2018, 501-505).

Žarana Papić is one of the present spirits I preserve vivid images of. I remember Žarana Papić also from the days I was a refugee in Belgrade, we moved in the same spaces and occupied the same streets while protesting. She was gentle and looked like a quiet woman, but she was not, she was just careful and gentle towards us, the new generations lost in the war.

As an active participant in the feminist anti-war movement of the 1990s in the region of former Yugoslavia and as somebody who met and lived the 90s together with women like Neda Božinović and Žarana Papić, my motivation to mention and remember, to dance with them and much more is huge, especially in the art institutions in Austria, as these are the spaces in which I often move as an artist and which are not immune to the past. Many artists have already written about the National Socialist policies of these very institutions in the time of the WWII and afterwards.2

Moreover, the motivation for this work stems from an observation of the continuities between different struggles of women in different historical periods, especially being aware of the patriarchally imposed discontinuity of the documenting and archiving of women's history. There are so many gaps and holes in between, so many unwritten or hidden testimonies that circle around as ghosts.

War after war imposed new discontinuities, existing history was erased, and historical revisionism became more prevalent, particularly in the period following the increased nationalism of the individual states in the 1990s. Due to the inextricable links between women’s role in society and the political transformations in the region, there would be be an "infinite circle of rediscovering and forgetting women’s history, emancipation, and a renewed reemergence from an endless source of patriarchal roots and relations and values, which have become all the more savage with each historical epoch.“ (Milić, 1998, 558)

And as Neda Božinović put it: “Feminism is one of the most important revolutions of the 20th century. We have a duty to communicate to each other the thoughts and deeds of women who opened spaces for women's freedom and autonomy.” (Božinović, 2000)

The ongoing female archive in Bosnia and Herzegovina3 inspired me and gave me the strength to talk about my female ancestors, because it is an almost forgotten story in my family and today it stands as a tension in the rooms and corners of abandoned houses, along with the bitten crochet milieus.

The only living witness from the Second World War period in my family is my mother's aunt Dobra, whom I interviewed in 2019. She told me: “After my father and uncles were deported to Jasenovac concentration camp (1942) my older sister Savka spent her days standing at the gate of our house secretly, she waited for a partisan troop to pass through the village so that she could join them. At the time Savka was 16 and I was only 14. One day the word was spread among the sisters, Savka ran away from home and went with a Partisan brigade in an unknown direction. She never came back. After word spread that Savka ran away, her sisters Zora and Rada were crying because they also wanted to join but had not managed as their mother was keeping an eye on them. We lived in fear and in silence, we were just waiting for the war to stop. Once the war was over, with the massive organization of AFŽ (Anti-Fascist Women Front), the rest of the sisters joined the movement. Zora and Rada joined the Youth Work Action in the construction of the railway Brcko-Banovici. Gina taught local women in the Vvillage to read and write. Mira moved to Belgrade and became active in SKOJ. Jelena moved to Tuzla and was part of an initiation group of AFŽ Tuzla and gave lectures on literacy. Ruza was also an activist withof AFŽ and kept in contact with other groups in the region. She regularly went to Sarajevo to join AFŽ meetings“.4

Today we can find many other examples of partisan women, about their forms of resistance. Each of these examples shows in its own way that women in former Yugoslavia paved new paths of freedom in a courageous and, I would say, performative way.

Lepa Radić and Marta Paulin Brina are only two examples of women in resistance, whose photos are circulating today on the Internet and about which there are various anecdotes.

Lepa Radić was just 15 years old when the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia in 1941 when she joined the Yugoslav Partisans in the fight against the Nazis —a fight that ended in her execution at just 17.

Marta Paulin Brina was one of the first representatives of Slovenian contemporary dance art. During the war, she joined the National Liberation War, where she was given the partisan name Brina. Aldo Milohnić, a theoretician of performance, wrote about a photograph of Marta Paulin, during her solo dance performance for a group of partisan fighters, referring to it as being part of “Choreographies of Resistance” (Milohnić, 2013, 15-20).

In the history of political struggles in the former Yugoslav region, women have always fought alongside men. This often overlooked history is significant because these struggles took place at the same time as fights for gender equality. In the 1990s, women’s struggles were anti-war, anti-fascist, explicitly feminist and leftist, and, furthermore, integrated into the cultural landscape of the communities. Anti-war protests were enacted as artistic performances in public space, and these explicitly-labeled performances echoed many women’s actions of previous generations, which were themselves often not identified as cultural phenomena at the time. However, when read from contemporary feminist and queer theories, they can very clearly be understood as performative—in both the sense of enacting an artistic performance as well as in regard to the very understanding of gender itself as performative.

Kozaračko kolo, a dance that I reenact in my performance in a form of solo dance, was originally danced in a big group. In my feminist reinterpretation, it becomes a ritual, taking place in the here and now, within Austrian art space.5 Body movements in Kozarčko kolo are rather rough and rigid, which connects me to the images of the ancestors, of peasant women who did hard work in the fields, who were active participants in the partisan resistance, and were also active in the post-war reconstruction of the devastated country, obtaining rigid and solid bodies that resembled stones and mountains.

Instead of Kozaračko, I called it Partisan Solo. It is a reminder and a recall, in the era of individualism, for collectivism and solidarity. It is the call to protest, to take the streets which we may need more than ever, as history is repeating.

Footnotes

1. These were VBKÖ / Vereinigung bildender Künstlerinnen Österreichs (2019), Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien (2022) and Kunstraum Innsbruck (2023).

2. Vinko Nino Jaeger in the History Channel (2019), https://www.vnjaeger.com/projekte/history-channel

Plattform Geschichtspolitik in the art work Kaiserrelief, Spatial intervention (2010) http://www.eduardfreudmann.com/?btx_portfolio=kaiser relief

Projects on VBKÖ Archives and History, Collection of 26 artistic and research projects that have critically dealt with the archive of the VBKÖ, the Nazi past and post-colonial and racist practices (since 2004) https://www.vbkoe.org/kritische-archiv-projekte/?lang=en

3. Arhiv Antifašističke Borbe Žena Bosne I Hercegovine I Jugoslavije: https://afzarhiv.org

4. Unpublished. From my private archive, my interview with Dobra Katić, 2019.

5.Antifascist journal - Text of the song of Kozaračko kolo: https://www.antifasisticki-vjesnik.org/hr/pjesme/8/Oj_Kozaro_/360/

Quotes

Zaharijević Adriana, “The principle is to cross the borders”. In The Never-Ending Quest for Sense: Woman and Peace building in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. Ed. Zlatiborka Popov-Momcinović and Adriana Zaharijević. Publisher Jelena Santić Fondation, 2022.

Stojanović Dubravka, To Cross Borders Daily. In The Never - Ending Quest for Sense: Woman and Peace building in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. Ed. Zlatiborka Popov-Momcinovic and Adriana Zaharijevic. Jelena Santic Fondation, 2022.

Donert Celia, Kerenji Sabina, Kulick Oryisia, and Lorand Zsofija. Unlocking new histories of human rights in state socialist Europ, The Neda Božinović and Žarana Papić Collections at the Library of the Women’s Studies Centre in Belgrade, COURAGE connecting Collections, 2018.

Anđelka Milić, Patrijarhalni poredak, revolucija i saznanje o položaju žene [Patriarchal Order, Revolution and Knowledge on Position of Woman]. In Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima 19. I 20. Veka – 2, Položaj žene kao merilo modernizacije: naucni skup, Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije, Beograd [Serbia in Modernisation Processes in 19th and 20th Century – 2, Position of Woman as Measure of Modernisation: The Conference]. 1998.

Božinvić Neda, The continuity of the struggle for peace and women's rights docu., Žene u Crnom production 2000.

Milohnić Aldo, Choreographies of Resistance. In Social choreography. Bilingual issue of TkH (Walking Theory). Journal for Performing Arts Theory, no. 21. Ed. Bojana Cvejić and Ana Vujanović. 2013.

Bibliography

Božinović, Neda. 1996. Žensko pitanje u Srbiji: u XIX i XX veku. [Women’s Issue in Serbia in the 19th and 20th Centuries]. Beograd: "Devedesetčetvrta": "Žene u crnom", Beograd: Pinkpress.

Đurović, Smiljana. 1998. Istorija žena – opšta metodološka razmatranja sa osvrtom na Jugoslovenski istorijski prostor u 20. veku [Women’s History - General Methodological Considerations Reflecting on Yugoslavian Historical Space in the 20th Century] and Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima 19. i 20. veka – 2, Položaj žene kao merilo modernizacije: naučni skup [Serbia in the Modernization Processes of the 19th and 20th Century - 2, The Position of Women as the Merit of Modernization: a Scientific Conference], Institut za noviju istoriju Srbije, Beograd.

Gržinić, Marina. 2000. Fiction Reconstructed. Eastern Europe, Post-socialism and the Retro-avant-garde. Vienna: Edition selene.

Gržinić, Marina and Stojnić, Aneta. 2014. “From Feminism to Transfeminism: From Sexually Queer to Politically Queer“. In Sexing the Border: Gender, Art and New Media in Central and Eastern Europe, Katarzyna Kosmala, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Kecman, Jovanka. 1978. Žene Jugoslavije u radničkom pokretu i ženskim organizacijama: 1018-1941 [The Woman of Yugoslavia in the Worker´s Movement and in Woman´s Organisations, 1918-1941]. Belgrade: Narodna Knjiga/ Institut za savremenu istoriju.

Milevska, Suzana. 2010. Gender Difference in the Balkans: Archives of representations of gender difference and agency in visual culture and contemporary art in the Balkans. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

Močnik, Rastko. 2016. The Partisan Symbolic Politics. In The Yugoslav Partisan Art. SLAVICA TERGESTINA European Slavic Studies Journal VOLUME 17. Trieste, Konstanz and Ljubljana: Università degli Studi di Trieste, Universität Konstanz and Univerza v Ljubljani.

Pavićević, Borka. 2018. "Testimony Borka Pavićević". In Theatre in the Context of the Yugoslav Wars, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Palgrave Macmillan.